When Lee Marvin put his price up to a million dollars a picture, he found it harder to get work

As I walk into James Garner’s suite at the Palisades Hotel in Vancouver, British Columbia, I suddenly feel as though I’m the Dude From the East accidentally strolling into the back room in Black Bart’s Saloon. There, sitting around a table in the kitchen, is Bret Maverick himself, surrounded by four other poker-playing rascals, and all of these boys are big.

We’re talking teamster big, with hair that looks like windblown bushes and sweaters that bulge with muscles, and not your smooth, sinewy account-exec Nautilus muscles, either. No, these guys are North Country big, with muscle and flab and big, flat faces, and they’re all smiling at none other than Gentleman Jim Garner himself, who turns and looks at me with that Jim Rockford “Awww hell, Angel” smile and says, “Now isn’t this just my luck. Just when I’m getting ready to take these suckers for every dime they got in a fast little game of Jerry’s Rules, I have to do this damned interview. Well, hell, on the other hand, maybe we got us here what you call your one more basic pigeon. Get yourself a drink of wine from the box in there, Robert, while I finish up this hand.”He’s up here filming Joseph Wambaugh’s novel The Glitter Dome for HBO, and Garner is all smiles as he invites me in. There is that born confidence man’s charm in his voice. “You get your wine, Robert?” Garner asks as he laughs and deals the boys another hand. “You know these journalists, they do like their booze.”

“Now just a minute,” I say. “Is this going to be one of these star-insults-the-press interviews?” Garner had already informed me that he does only one interview a year, and this is it. (“Hell,” he’d pointed out, “I don’t even eat with my press agent.”)

“No way, no way,” Garner says, smiling and winking and raking in the chips with his big, meaty right hand. “What we got here is an I-treat-you-like-a-king interview. We’re talking your basic royalty on the road. Man came all the way from that behavior sinkhole New York City to talk to me, boys, so I’ll have to do some work. I don’t know why anybody would want to know what the hell I have to say anyway, but as long as he’s here, we’re going to treat him right.”“Just make sure you teach him Jerry’s Rules,” says Dave, a muscle-bound kid with a big, innocent face. “I still don’t understand that goddamned game.”“In good time,” Garner says. “All in good time, Dave. Just make sure you get us out there to the location in that damned snow tomorrow, okay?”As I walk into James Garner’s suite at the Palisades Hotel in Vancouver, British Columbia, I suddenly feel as though I’m the Dude From the East accidentally strolling into the back room in Black Bart’s Saloon. There, sitting around a table in the kitchen, is Bret Maverick himself, surrounded by four other poker-playing rascals, and all of these boys are big. We’re talking teamster big, with hair that looks like windblown bushes and sweaters that bulge with muscles, and not your smooth, sinewy account-exec Nautilus muscles, either. No, these guys are North Country big, with muscle and flab and big, flat faces, and they’re all smiling at none other than Gentleman Jim Garner himself, who turns and looks at me with that Jim Rockford “Awww hell, Angel” smile and says, “Now isn’t this just my luck. Just when I’m getting ready to take these suckers for every dime they got in a fast little game of Jerry’s Rules, I have to do this damned interview. Well, hell, on the other hand, maybe we got us here what you call your one more basic pigeon. Get yourself a drink of wine from the box in there, Robert, while I finish up this hand.”He’s up here filming Joseph Wambaugh’s novel The Glitter Dome for HBO, and Garner is all smiles as he invites me in. There is that born confidence man’s charm in his voice. “You get your wine, Robert?” Garner asks as he laughs and deals the boys another hand. “You know these journalists, they do like their booze.”“Now just a minute,” I say. “Is this going to be one of these star-insults-the-press interviews?” Garner had already informed me that he does only one interview a year, and this is it. (“Hell,” he’d pointed out, “I don’t even eat with my press agent.”)“No way, no way,” Garner says, smiling and winking and raking in the chips with his big, meaty right hand. “What we got here is an I-treat-you-like-a-king interview. We’re talking your basic royalty on the road. Man came all the way from that behavior sinkhole New York City to talk to me, boys, so I’ll have to do some work. I don’t know why anybody would want to know what the hell I have to say anyway, but as long as he’s here, we’re going to treat him right.”“Just make sure you teach him Jerry’s Rules,” says Dave, a muscle-bound kid with a big, innocent face. “I still don’t understand that goddamned game.”“In good time,” Garner says. “All in good time, Dave. Just make sure you get us out there to the location in that damned snow tomorrow, okay?”The next day, after a morning of playing backgammon and shooting craps with Garner and his stand-in/best buddy for thirty-seven years, Luis Delgado, I’m in Garner’s van, heading across Vancouver for a graveyard scene. It’s getting cloudy and dark out, and Jim Garner is talking about his past, honesty and Hollywood.“You see,” he says, flipping down his shades and looking out at the streets, “I was raised in a place where a man’s word was his bond. Oklahoma. Oh, sure, we had our hustlers there too, but for the most part people were honest, took care of one another. If a man lied, it was usually transparent, because the norm was to tell the truth. But in L.A. people live the lie. They’ll look you right in the eye and lie to you. They lie even when there’s no reason to. I don’t understand those people. They’re too devious for me. I don’t trust any of them anymore. They’ve taken the heart out of it for me, and I used to really love this business.”I ask if he’s referring to the multimillion-dollar lawsuit against Universal over The Rockford Files, in which Garner is suing to retrieve profits from the series.“Some guys are professional, too professional, so they get slick and use the same old tricks. But Jim is working on making it real, rougher around the edges.”

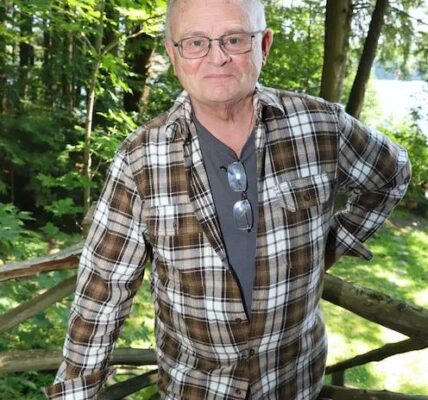

“Yeah, among other things. Our company, Cherokee Productions, was supposed to get a 38 percent share of the profits. We brought that series in only seven days over schedule in five and a half years—no other television show can match that record for even one year. The show was a big, big hit. I figure they’ve stolen about 25 million dollars from me, and that’s a hell of a lot of money.”He then begins to patiently explain the elaborate and varied tricks accountants can play to somehow conclude that a show that was a hit for six years, and is still in syndication, didn’t earn a dime and is, in fact, $9.5 million in debt. “I don’t know if I’ve got the guts to resist the out-of-court settlement when they offer me a whole bunch of money to call it off,” Garner admits.“Is it worth all the mental aggravation?” I ask.“Now you’re talking like them,” Garner says, and there’s steel in his voice. “They figure to wear you down. But damn, it’s not just that they have my money, it’s also the principle of the thing. It’s wrong.”There’s a finality to the word wrong, and I have to smile. I think of Martha, a southern lady I know who’s a secretary in Baltimore. When I told her I was going to interview James Garner, she said, “You tell him he has an honest face and he’s the only damned movie star I’d move back into a trailer with, you hear?”At a freezing suburb outside Vancouver that has been dolled up to resemble L.A., Garner gets dressed to play a tough scene. He plays a burned-out detective in The Glitter Dome. A buddy has been killed, and Garner has to stand at the funeral in the “rain” (supplied by off-camera hoses with sprinklers attached) and look as though he’s been beaten down by exhaustion and drink and fatigue. As I wait for him to change his clothes I talk to Stuart Margolin, the director. He’s best known, though, as Angel, Jim Rockford’s squealing, bitching, cowardly but lovable buddy-nemesis on The Rockford Files.We huddle up in a truck cabin, eat some cold chili and talk about Garner’s acting.“He’s getting better and better as an actor,” Margolin says. “I mean, some guys are professional, too professional, so they get slick and use the same old tricks. But Jim is working on making it real, rougher around the edges. The next ten years should be interesting. He’s turning the corner into what you call the leading character man. He’s going for more experimentation, and he’s brought a reality all his own to this part. You watch these scenes, and you’ll see what I mean. This isn’t Maverick.”A few minutes later I watch Garner standing on the freezing infield of a Vancouver playground. The water is coming down on him, and the camera closes in, and there is pain, disgust, weariness, that does look different from anything I’ve seen from him in the past. It’s the face of an older, hurt man, and I think that maybe, unconsciously, he’s using the lawsuit against Universal to summon these feelings of disgust and anger. But whatever is pushing him forward, it’s obvious that he’s going for something different here, something that reaches the gut in a deeper way than charm.Now, in the darkness, we’re riding across Vancouver. Our friend Dave the driver has stopped by the van and assured us there’s not going to be any snow, but it’s already falling, great thick flakes. All the world’s a great, soft stage, and only the hum of the van’s engine cuts through the night as Garner rides shotgun and Luis and I sit in the back in a warm, comfortable and friendly haze.“I read somewhere that you never let your price get too high for films,” I say. “Why’s that?”“Well,” Garner says, turning around and putting one leg up on the tool hump, “in Hollywood they have this terrible thing: You can’t ever let your price go down When Lee Marvin put his price up to a million dollars a picture, he found it harder to get work. I didn’t want to cut myself out of work, so I never let it get that high. I mean, if a picture is really good, I’ll do it for practically nothing, take a little profit on the back end.”“Have you ever really done that?” I ask.At 55, his knees are shot, the result of several operations and arthritis, but otherwise he looks great, and later I ask him if he works out at all. After an appropriate pause, he says, “The only time you’ll see me jogging is if somebody is chasing me—and he better be big, or I won’t even run.”

“Sure. I did it for Bob Altman on Health, which is a pretty good though hardly anybody saw it. But I did it because I wanted to work with Altman, and Betty Bacall and Glenda Jackson, and Carol [Burnett] and Cavett… yeah, even Dick Cavett, he’s my buddy. I talked to him the other night, and I confessed to this little trick we played on him. See, Betty Bacall wrote up this diary, invited Cavett over to her condo and left it out especially for him to see. Then she goes into the bedroom, and she leaves the diary there, wide open. Well, he can’t resist taking a peek, and suddenly he sees his name. Now he’s got to read it, and it says something like, ‘Well, Jim Garner is such fun, and Carol Burnett Is a ball and Glenda Jackson is wonderful, but Dick Cavett dresses like a 14-year-old and is so silly.’ And it just crushed him. Well, he finally admitted when I talked to him the other night that he had seen the diary, and I say, ‘Did it ever occur to you that that diary was put out there so you would see it?’ And he says, ‘You wouldn’t…. I went to therapy over that!’ And I said, ‘Well, Dick, maybe I would and maybe I wouldn’t!’” Garner slaps his thigh and laughs hard and loud. The kind of joke Bret Maverick might like.As we arrive at the big studio on the top of the snow-covered mountain in Vancouver, Garner is talking about the first time he met his buddy Margolin and about his favorite TV role.“We had this show called Nichols. It’s the best work I’ve ever done, about broke my heart. The show was set at the turn of the century, in Nichols, Arizona, and I played a sheriff who rode a belt-drive Harley Davidson and refused to carry a gun. Wore jodhpurs and cavalry boots, and Stuart played a variation of the character he later played on The Rockford Files. In Nichols, though, he was really the most back-stabbing, irritating sneak, and he was my deputy. Margot Kidder was in Nichols, too, and she was wonderful.“God we had talent on that show. Anyway, we were dead the first night we showed the pilot to the Chevrolet people in Detroit, because some executive’s wife didn’t like It. She said, ‘Well, that’s not Maverick!’ Well, of course it wasn’t Maverick! It was better than Maverick, humorous, with social satire. But we got preempted eight times out of twenty-four shows because of Nixon running for election. Then they moved us up against Marcus Welby, and we ran even with him, and he was the number-one show in the country. I don’t think we ever got below a 35 share the whole time. Hell, the show lasted one year, I swear to you, if they would have It on another year, it would still be running today. It was just too damned original.”Garner now walks in from the blizzard to play a scene in which he’s walking through a daytime L.A. drizzle. He puts on his L.A.P.D. overcoat and slides into the makeup room. Susan, a makeup girl, affectionately starts in about Garner’s hair.“It’s getting so long, dear.”“Well, darling,” Garner says, “I know you’ll make it wonderful.”It’s obvious that all the girls in the makeup department are crazy about him, each of them going out of her way to make him comfortable, bringing him mints (Garner is forever asking people for mints) or hot chocolate. Garner has such an easygoing manner, and there is never a hint of his demanding anything. Indeed , earlier today he mentioned a famous star whom he detested because he picked on little people on the set. “I won’t tolerate that,” he says. “My lawyer used to call me Crusader Rabbit! Bullying is not acceptable.” The line sounds very much like something one of Garner’s heroes, John F. Kennedy, might have said.“Earlier today I watched you do that scene at the graveyard,” I say, “and you looked an older, weary man. Do you worry about getting old?”“Nah, I think young.”“I watched you on Maverick when I was 5,” Susan says, and Garner playfully gives her a punch on the jaw.“She’ll do it to you every time,” he says. “Sneaky.”At 55, his knees are shot, the result of several operations and arthritis, but otherwise he looks great, and later I ask him if he works out at all. After an appropriate pause, he says, “The only time you’ll see me jogging is if somebody is chasing me—and he better be big, or I won’t even run.”“What about immortality?” I ask as we trudge from the makeup truck to the studio in the deepening snow.“What about i t?”“Is it any… consolation?”“Hell, no, not one whit. They could burn all the film tomorrow and I wouldn’t care. Listen, I’d rather be remembered in literature, anyway. Yeah, I was mentioned in Myra Breckenridge. Gore Vidal wrote that his hero had ‘inspected all the cowboy heroes’ asses, from the flat ass of Hoot Gibson to the impertinent, baroque ass of James Garner.’ Hell, I can be remembered for that.”We both laugh, and Garner shakes his head.“Man, I had to go look in the dictionary to figure that one out.”“And what did it mean?” I ask.“I don’t know,” Garner says as we walk into the studio, “but it sticks out and it’s got dimples.”By Robert Ward 1984